Cages and Conundrums

How Wes Anderson's 2009 Fantastic Mr. Fox adaptation absolutely nails our modern existential crisis of wildness and conformity

You’re probably familiar with the famous Roald Dahl story Fantastic Mr. Fox — the whimsical tale of a clever fox who outsmarts three terrible farmers in order to feed his family. Or maybe you’re more familiar with Wes Anderson’s 2009 film adaptation, featuring the ensemble cast of George Clooney, Meryl Streep, Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Willem Dafoe, and Owen Wilson… with Anderson’s trademark dry wit and vibrant, in this case, autumnal color palate.

But what far fewer might realize is that Anderson’s adaptation is one of the most richly and deeply layered allegories for the cognitive dissonance and internal personal conflicts associated with modernity and widely-held belief systems. More specifically, it is an allegory for modern professionals or those navigating societal expectations in reconciling the security of the traditional “day job” mentality with the restless impulse to forge one’s own path and honor one’s wild or entrepreneurial nature. Beneath its stop-motion charm and quippy dialogue lies a remarkably profound commentary on the modern condition. We have built a world where the wild animal in all of us struggles to survive within systems designed for routine, compliance, and performance in which we never break the fourth wall on our own stories.

This essay has been years in the making. The movie was released in 2009 — the same year I graduated college and kicked off my adult life and career. You can say it’s been playing in the background in my head ever since… soundtrack and all.

The Cage

The film opens with a younger Mr. Fox (voiced by George Clooney) standing on a hill, sporting this slick corduroy jacket (no tie, which is a crucial detail), biting into an apple he just plucked from a tree. He’s sporting a Walkman-like radio clipped to one of his jacket pockets, blaring the song “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” by The Wellingtons. It’s a 1950s TV theme song with lyrics like, “Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee,” “Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier,” “the man who don’t know fear”… which evoke this legendary frontiersman character and mirrors the rugged individuality Fox himself seems to embody. He’s waiting for his wife or girlfriend, Felicity (Meryl Streep), to join him on what turns out to be a daring heist to “steal birds,” as they call it. Felicity arrives in bohemian attire — a loose shirt and a ‘60s-esque headband — and her style, Fox’s, and the song give this vibe of total freedom… no kids, no jobs, just taking from the world — or the system — as needed to survive.

Then the scene shifts to a fast-paced, distinctly stop-motion sequence of spry, little clandestine movements. They hop from tree to rooftop to wheelbarrow, infiltrating the outer fence enroute to the squab shack, where they swiftly kill a few birds. Meanwhile, the music accompanying the scene is The Beach Boys’ “Heroes and Villains,” which is one of the most layered songs ever written by Brian Wilson (who passed this year — RIP). I’m not sure if Anderson intended this level of depth, but the song was born from Wilson’s own painful self-discovery period. Raised in a deeply religious household, Wilson began questioning dogma, traditional structures, and the very concept of belief systems. The consensus interpretation of the song seems to be that Wilson wanted to expose America’s folksy admiration for its origin stories by revealing the more nuanced reality rarely acknowledged in common discourse — that there’s no black-and-white good or evil, that heroes and villains are intertwined, and that that we’d better accept this rather than craft comforting narratives for ourselves and for society.

A key lyric — “Heroes and villains, just see what you’ve done”— foreshadows the existential questions Fox ends up grappling with later in the film as he chases his identity and navigates major moral gray areas. And it captures the broader social commentary of defying corporate systems and their oppressive control while causing damage of your own in the process. And it frames Fox as a rebellious heroic outlaw in a world that cages him, both figuratively and, at first, literally…

As Fox and Felicity plot their getaway after killing the squabs, Fox notices a mysterious chain dangling outside the squab shack. Despite Felicity’s pleading to get the hell out of there, his curiosity and bold ego prevail. He pulls the chain, knowing it connects to a trap but he’s confident it would be “spring-loaded” and fall “over there.” Nope. It drops straight down, trapping them both. Then they see the farmers running after them over the fence with pitchforks.

Felicity, ever composed, reveals she’s pregnant (they’re having a cub!), then she delivers a knockout line that sets the thematic stage for the entire movie…

“If we’re still alive tomorrow, I want you to find another line of work.”

That cage is a metaphor for the collision between wildness and modernity’s constraints. Fox’s impulse to pull the chain reflects his Crockett-like bravado, an entrepreneurial spirit to master his environment, echoing the song from the opening. But it doesn’t matter — those days are over. The cage is the price of defiance, but modern society offers a way out… with safety, stability, and structure in exchange for submission. But they literally have to dig out of the situation — a grueling and humbling experience — and remake themselves entirely in order to survive. It’s allegorical to the moment one goes off to college, signs a lease, takes a desk job, gets a mortgage, or otherwise commits to a predictable structured life. It’s a tragedy of entrapment, hinting that Fox’s wildness belongs to a bygone era, soon to be tamed by modern systems and contemporary expectations.

And it’s always the little details that speak the loudest. The cage reads: “Butler & Son" Wild Animal Destruction. The “system” in this story wants to kill the independent spirit.

The Cape and the Tailhole

Years later, Fox has traded his Walkman and cool corduroy for a short sleeve dress shirt and a striped tie — he’s “civilized” now. He lives in a modest fox hole and has a job at a local newspaper writing a column he thinks nobody reads. He and Felicity are raising their son, Ash (voiced by Jason Schwartzman). They’re the picture of domesticated life — morning breakfast routines, reading the paper, kids getting ready for school, a steady paycheck, and aspirational talk with your wife about moving up to a bigger house or better neighborhood.

Fox voraciously eats his breakfast literally like a wild animal then stands up to head off to work. As he turns around, we see his tail sticking out of a tail hole in his khakis. This is one of those subtle but profound elements of the scene and film — a perfect metaphor for the incomplete domestication of his wild self. Fox is donning the accoutrements of civilized life — the tie, the job he complains about, the family fox hole — but his true nature protrudes nevertheless. And his appetite remains uncontainable. Meanwhile, just as Fox is walking out the door, Ash walks out while brushing his teeth, but his outfit is ridiculous. Fox askes…

What are you wearing? Why a cape with your pants tucked into your socks?

Ash offers no response, just stares at his dad, and walks back into this room. Fox then turns to Felicity and says…

“I guess he’s just…. different.”

Then Fox leaves for work.

This whole scene speaks to “civilized” conformity and social expectations — the full-time job Fox needs to rush off to with its benefits and predictability, joking with his wife how his son is “different” implying that he’ll need to get his act together at some point if he wants to “fit in” like everybody else. Yet Fox himself is simmering with dissatisfaction about how his life has turned out by following those rules. Earlier in the scene he tells Felicity that living in their hole makes him “feel poor” and wonders “does anybody even read my column?” The scene is setting the stage for his own rebellion and the risks it will bring to both himself, his family, and his entire community.

The Whack-Bat Pitch

There’s a subplot in the movie involving Fox’s nephew, Kristofferson (voiced by Wes Anderson’s brother Eric) coming to stay with them for awhile because his father is undergoing treatment for an illness. Kristofferson is this stoic and soft-spoken prodigy kid with perfect athleticism who can apparently master any sport just upon hearing the rules one time. He knows kung fu and he meditates. He’s the polar opposite of the unrefined rough-around-the-edges Ash who’s “different.”

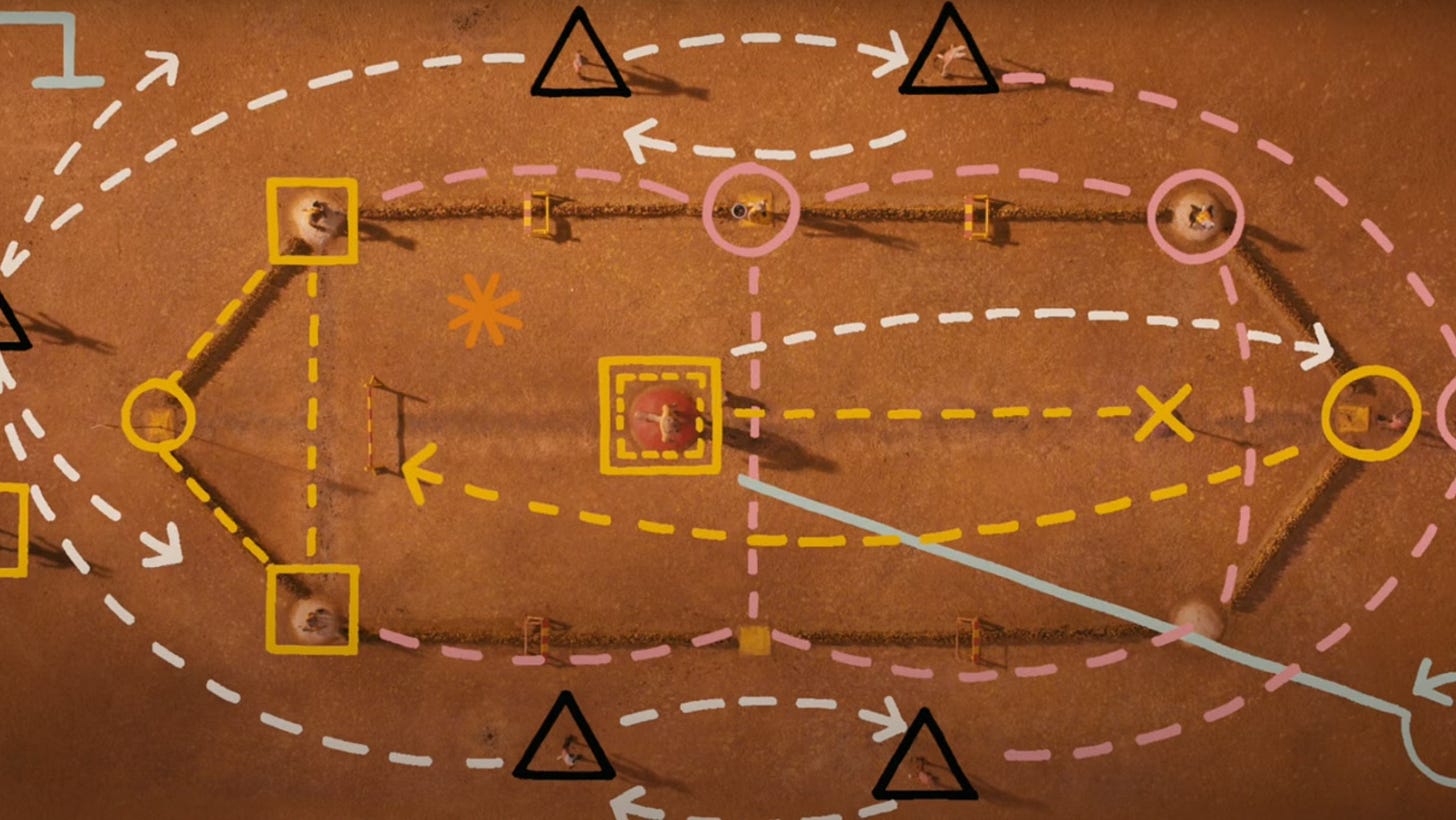

Then there’s a scene where Ash and Kristofferson are at the schoolyard playing a sport called Whack-Bat. It looks like a form of cricket or baseball, but with absurdly complex rules and rituals. Coach Skip (voiced by Owen Wilson) explains the rules to Kristofferson:

Basically, there's three grabbers, three taggers, five twig runners, and a player at Whackbat. Center tagger lights a pine cone and chucks it over the basket and the whack-batter tries to hit the cedar stick off the cross rock. Then the twig runners dash back and forth until the pine cone burns out and the umpire calls hotbox. Finally, you count up however many score-downs it adds up to and divide that by nine.

“Got it," says Kristofferson, immediately, and he runs in to sub for Ash.

Coach Skip then reminisces to Ash about how great a Whack Bat player Fox was: “Your dad was probably the best whack-bat player we ever had in this school.” Ash — yearning for validation — asks, “I think I have some of the same raw, natural talent, don’t you?” to which Coach Skip tells him he’s improving and let’s “leave it at that”.

Of course, Ash isn’t satisfied and it doesn’t help that Kristofferson, who just subbed in to the game for Ash, is instantly incredible despite having learned the rules 10 seconds ago. The exchange reveals Ash’s insecurity about his identity and the burden of his father’s legacy, but it also introduces a broader allegory. Whack-Bat is a proxy for how society creates entirely arbitrary and borderline silly rules we must perform to attain modern achievements. With its opaque scoring and theatrical elements, Whack Bat mirrors the bureaucratic absurdities of modern life and careers — standardized tests, curriculums and extra-curriculars, tax laws, ordinances, corporate KPIs, LinkedIn profiles, annual performance reviews, forced team building exercises, compliance seminars, alphabet soup credentialism, etc. It’s a game designed for conformity, rewarding those who master its rules over those who play with necessarily any heart, purpose, or individual identity or expression.

Ash struggles not necessarily because he lacks talent, but because he’s trapped in a system that doesn’t value his quirky “different” spirit. The system punishes uniqueness, demanding assimilation at the cost of authenticity.

Now enter Kristofferson who complicates this whole dynamic. Poised and naturally gifted, he excels at Whack Bat with acrobatic moves and unbelievable precision, yet he does it all casually and is indifferent to accolades — practicing meditation and martial arts in quiet defiance of any overly competitive disposition or ethos. Kristofferson then seems to embody this kind of a perfectly balanced ideal, someone who navigates systems without being consumed or defined by it, using his superior ability and instincts while maintaining discipline and sitting quietly in deep introspection instead of leaning too hard into those gifts. His wise-beyond-years internalization contrasts with his cousin Ash’s internal identity crisis and his uncle Fox’s external one, suggesting a kind of “third path” through life — wildness tempered by wisdom — that neither Fox or Ash fully achieve until the end of the film.

The Charade

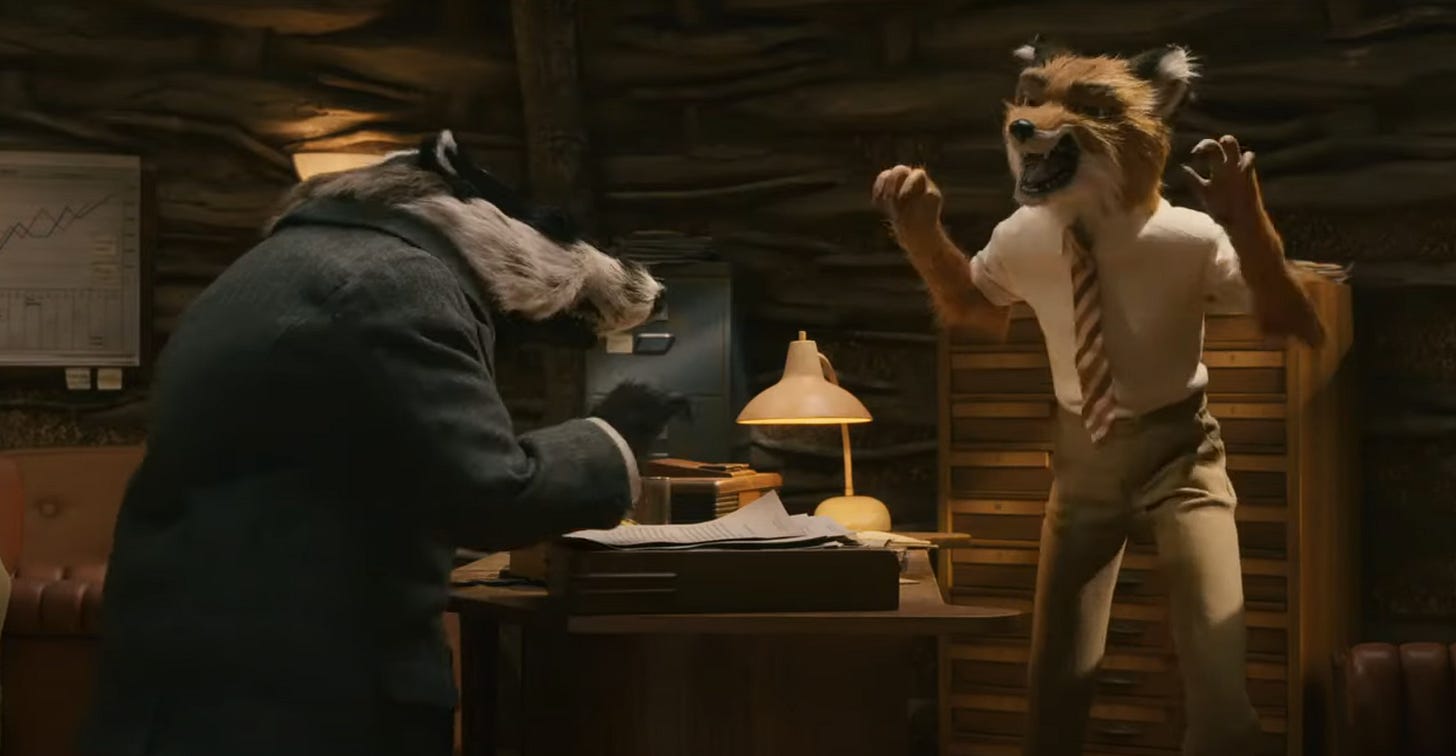

Before Fox’s recidivistic rebellion fully kicks off — when he starts sneaking off from the family late at night to “steal birds” — there’s a pivotal scene that reveals the hollow bravado of domesticated wildness. Fox is restless and eager to move his family up in the world — to the larger more stately beech tree which is for sale in a better neighborhood. He meets with Badger (Bill Murray), his lawyer and personal friend, in Badger’s office.

As they discuss the sale, Badger voices his opinion that Fox shouldn’t buy the tree. He explains how the beech tree is in the most dangerous neighborhood as it overlooks the three cruelest, greediest, ugliest farmers in the entire valley — Boggis, Bunce, and Bean. The two erupt into this primal display of growling and snarling at each other, chasing each around around Badger’s desk like wild animals. It’s a flicker of their core wild animals breaking through. But then, just as abruptly, they stop. Fox, regaining composure, says flatly, “Just buy the tree.”

“OK” Badger says, defeatedly… exhausted.

The scene is a masterstroke of allegory because it exposes the performative nature of wildness within the confines of our “safe” modern systems. Fox and Badger, both suited professionals in a civilized office, play at being wild — growling, posturing, indulging in a fantasy of primal defiance. But that’s what it is, a fantasy. The office is a safe space, insulated from any real risk. No farms are raided, no cages are sprung. Their growling is a charade, a way to vent their instincts without threatening their comfortable lives. When Fox calms down and says, “Just buy the tree,” he snaps back to the script of domesticated life and acquiesces to the system’s demands — more polite decorum, purchasing property, signing contracts, playing the game.

The moment can mirror the “tough talk” of highly paid corporate professionals —bankers, lawyers, or executives — who boast of their boldness or independence while remaining tethered to their traditional jobs or positions in society. They might rail against the system in boardrooms or bars, flaunting their ambition or grit, but how tough are they really? Their rebellious attitudes are performative, confined to safe spaces. Like Fox and Badger, they ultimately “buy the tree,” conforming to the system’s expectations… taking the promotion, moving to the nicer neighborhood, signing the non-compete, and staying in the proverbial cage. This growling scene underscores the film’s critique of modernity, which allows us to mimic wildness, but only as a performance, never as a true break from the leash of expectations.

The Tree

On the surface, buying the beech tree is a step up. It’s a much a grander home, has a better view, and is a symbol of success. Remember Fox told Felicity, “I don’t want to live in a hole anymore. It makes me feel poor.” So beneath his ambition lies deeper concern about his identity and standing within the modern economic system. It mirrors the mid-career crisis of many professionals today. After years of climbing the corporate ladder, providing for a family, and checking societal boxes, they feel a little hollow because perhaps they’ll always want more. But they didn’t build the system they’re navigating — they rent a space within it. That beech tree, which is perched dangerously close to the farmers’ domains, symbolizes both this aspiration and the risk. From his new vantage point, Fox can see the farms — Boggis’s chickens, Bunce’s geese and ducks, Bean’s turkeys, apples, and cider — and his wild instincts stir. The view isn’t just scenic, but palpably tempting. It’s reawakening his entrepreneurial urge to take, to master, to reclaim freedom and “wildness” for himself.

Of course, this causes major issues at home. Felicity senses the danger in Fox’s restlessness, and we see this foreshadowed somewhat in what she’s often painting in the background of one of the scenes — a lightning storm. When she later confronts Fox after his secret heists endanger their family, she slashes him in the face and says, “I love you, but I shouldn’t have married you.” Her pain is raw and she wonders what she got herself into. She embodies the cost of Fox’s rebellion — caught between loving his wild spirit and needing stability — something that might feel familiar to so many couples and families today.

So, the beech tree is the crossroads where Fox’s successful domesticated life meets his untamed, unfulfilled desires. It amplifies the tension between performance (growling in the office) and true risk (actually raiding the farms).

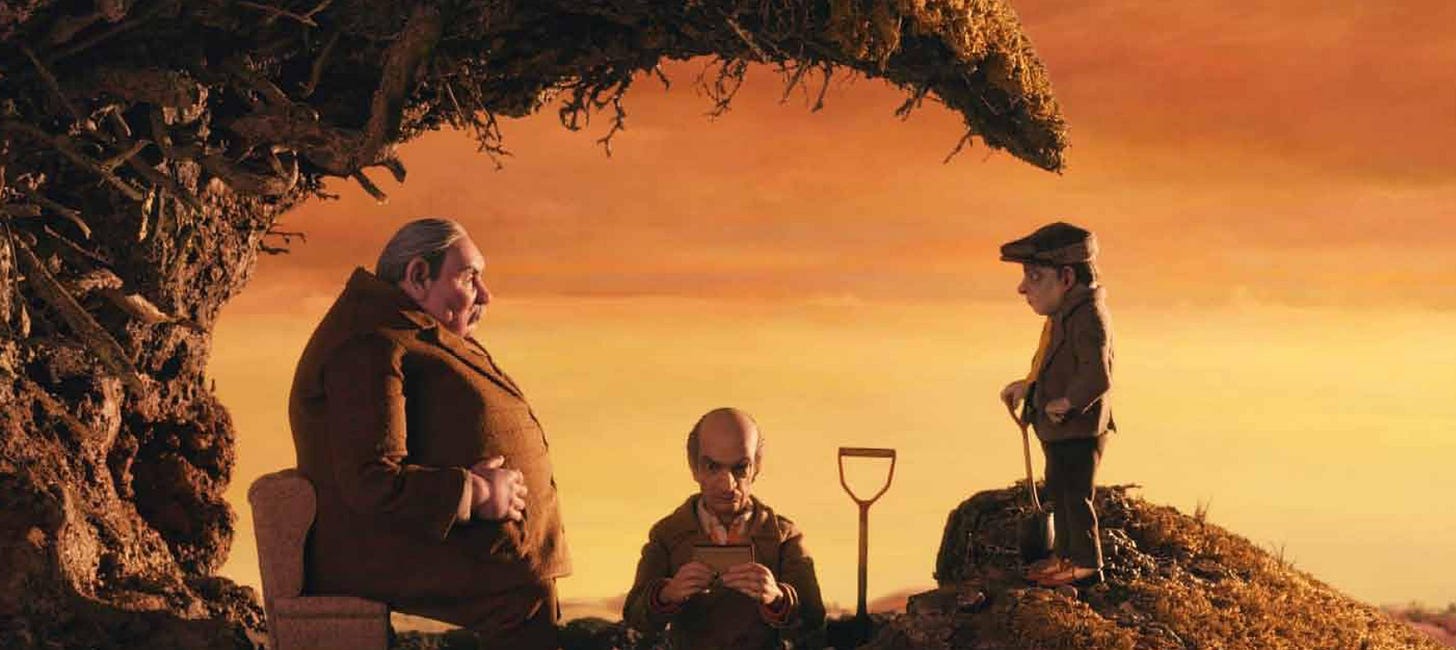

The Farmers

Boggis, Bunce, and Bean are the most cartoonish villains. And they’re the anthropomorphs of “the system” and its oppressive power. Each has a distinct characteristic. Boggis is a glutton. Bunce is paranoid. And Bean is ruthlessly cunning. Together, they form a monolithic force that demands compliance and punishes any deviation from their order. Their farms — with fortified electrified perimeters and mechanized efficiency — symbolize the industrial roots of modern labor. Centralized control, closely monitored, and hostile to outside disruption.

When Fox resumes his heists — stealing from their farms, shacks, and stockpiles — the farmers retaliate with escalating levels of violence. They bring bulldozers, dynamite, snipers, and effectively militarize their entire personal staffs. They start tearing apart the landscape to root out Fox, his family, and his entire community.

They shoot off Fox’s tail and destroy the beech tree. Losing his tail is an act of humiliation and a demonstration of the system’s power and motivation — to suppress and domesticate dissent.

The siege that unfolds, particularly the digging excavators that trap them underground, feels like corporate modernity crushing the natural world. The farmers’ willingness to destroy their own land to maintain control mirrors how bureaucratic systems — corporations, governments, HR departments — prioritize dominance over creativity or individuality. Fox’s rebellion threatens their order, and they’ll stop at nothing to enforce it.

The Rat & The Opossum

In Bean’s cider cellar, Fox confronts Rat (Willem Dafoe). Rat is this slick switchblade-wielding traitor who works for Bean guarding his cellar from intruders. Here’s their exchange.

Fox: You've aged badly, Rat.

Rat: You're getting a little long in the tooth, yourself, partner.

Fox: Bean security, what? Why are you wearing that badge? What is it?

Rat: It's my job.

Later in the film, the farmers have forced the entire animal community underground — digging frantically from one hole to another to avoid the diggers — before flushing them out (with cider) leaving them to cling to survival within the city sewers. In the meantime, Ash and Kristofferson had gone and broken into Bean’s house to retrieve Fox’s shot-off tail, which Bean was keeping as a trophy and literally wore as a neck tie. They failed. Ash got away but Kristofferson was captured and put in a cage. So Fox, Ash, and their friend Kylie the opossum are trying to get him back.

In the sewer, Fox and the gang confront Rat again, who’s been hunting them down. Fox and Rat fight to the death. Fox wins, and he kneels down beside Rat in his last moments…

Rat: The boy's locked in an apple crate on top of a gun-locker in the attic of Bean Annex.

Fox: Would you have told me if I didn't kill you first?

Rat: Never.

Fox: All these wasted years. What were you looking for, Rat?

Rat: C...

Ash: He's trying to say something, Dad.

Rat: Cider.

[Fox grabs some sewer sludge — the cider which had flushed them out turned to a sort of jam]

Fox: Here you are, Rat. A beaker of Bean's finest secret cider.

[Rat licks the sludge.]

Rat: Like... melted gold.

Then Rat dies.

This is another powerful moment. Rat didn’t betray his animal kind for power or ideology but for comfort — the addictive lure of stable luxury. The “golden handcuffs” you could say. He sold his soul for a steady drip of cider, becoming a cog in the farmers’ machine. Rat is the ultimate company man — compliant, well-fed, secure, and spiritually hollow. His fate warns Fox — and us — of what happens when your wildness or true identity is fully traded for perks and the illusion of stability. Fox gazes at Rat with mournful pity, perhaps recognizing a shared temptation. The cider is the system’s bribe, and Rat’s death mourns those who take it.

Kylie (Wallace Wolodarsky), Fox’s opossum sidekick, offers a much lighter allegory. His trance-like loyalty — just shrugging when asked if he’s following along or lines like — mirrors the employee who follows orders without questioning, numbed by their day-to-day routine and processes. At one point, Kylie asks Fox, “Hey, I didn't get a job yet, or a Latin name. What's my strength?" Fox replies, "Listen, you're Kylie. You're an unbelievably nice guy. Your job is really, just to... be available, I think.” Whether intentional or not, that line in particular speaks to a theme I write about very often — how performative most corporate “W2” jobs are today and how a significant proportion of a corporate paycheck is just “being available” for lack of any substantive need for you most of the time.

So Rat and Kylie frame the two opposing sides of the spectrum of modernity’s entrapment. One is seduced by rewards while the other is dulled by compliance. Fox, balancing rebellion and responsibility, sees his vulnerability in both their choices.

The Wolf

After Rat reveals where the farmers have imprisoned Kristofferson, Fox and team brilliantly battle their way through the farmers’ blockades and obstacles. Fox and Kylie then steal a motorcycle with a sidecar and head for Bean’s farm. On the way, Ash pops his head up, somehow sneaking along for the rescue, and ends up displaying incredible daring and heroism in his own way that ultimately saves them all from being trapped a few scenes later. They save Kristofferson, get away, and on the ride back they spot a lone black wolf on a snowy ridge in the distance.

Fox stops the bike, awestruck.

Fox to Wolf: Where did you come from? What are you doing here?

Fox to the others: I don’t think he speaks English or Latin.

Fox to Wolf: Pensez-vous que l’hiver sera rude?

Fox to the others: I’m asking if he thinks we’re in for a hard winter.

Fox to Wolf: I have a phobia of wolves.

Fox to the others: What a beautiful creature. Wish him luck boys.

The wolf hasn’t reacted or responded at any point.

Fox then raises his fist in salute. The wolf, silent and stoic, raises his in return.

This is one of Anderson’s finest moments.

Fox does have a phobia of wolves. The wolf embodies total freedom — unbound by cages, suits, or systems. It’s what Fox thinks he should be, perhaps wants to be, but knows he can’t ever be in the complete sense. He’s somewhere between the wolf — totally free and wild — and the dog — totally deferential and domesticated.

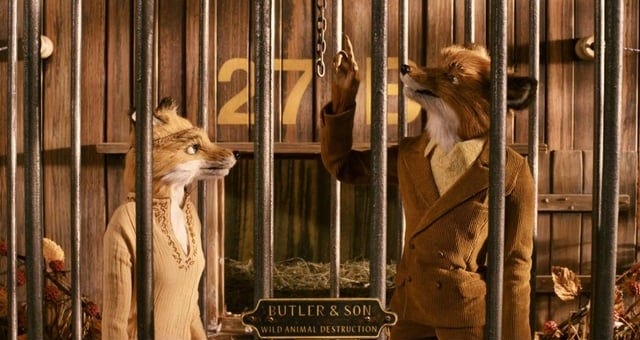

There’s a tiny little detail earlier in the film that’s impossible to pick up in the moment, but offers the film’s first major foreshadowing. It’s the scene where we get a brief glimpse of Fox’s newspaper column, and I included the screenshot above. If you pause and actually read it, you’ll notice some important lines.

The breeze picks up and a change of season comes upon us. Once again, we find ourselves savouring the dusky, smoke filled air, the sweetest of the year, and scampering about, even as hibernation awaits just ahead, tapping its impatient hind paws -- and so we return to the whack-bat pitch.

The column goes on about wolves and the inspiration for their team name.

I have never crossed paths with an English Wolf, but pardon my French they scare the cuss out of me. What sort of creature sleeps with the windows open? Answer, one with long claws and about ten stone on yours truly.

Fox is writing about life’s predictability and cyclicality, and about whack-bat which is the embodiment of the “whacky” rules-based order we’ve built around ourselves in modernity. And he’s reflecting on how scary it is to “sleep with the window open” like the wolf. To live with the unknown where anything can jump in and anything can fall out. To bring the weather inside. To be uncomfortable. Better to keep the windows closed and keep the climate controlled. And how you need, perhaps, to be or become a certain way. To build “stone” around yourself or develop claws in order to endure the winter snow if you want to enjoy the summer breeze.

In fact, Fox asks him exactly that. Does he think the winter will be harsh? And he asks in French! He’s asking almost as if he’s seeking confirmation that it will, in fact, be harsh… validating his growing acceptance that with his family, debts, and compromises, he can’t be the wolf.

The wolf symbolizes the non-conformist, the entrepreneur, the one who never signed on the dotted line, the one who never fully accepted modern society’s constraints or rules. And Fox honors him and shows him the deepest respect. The wolf is a reflection of who Fox might have been had he never made modernity’s deal — had he perhaps never pulled that chain and trapped himself and Felicity. The raised fist is as much of an admiration as it is a farewell. An acknowledgement that some freedoms, while incredible and beautiful, are out of reach for those tethered. The scene resonates with anyone who has glimpsed their wilder self — quitting their jobs, taking time to travel, to volunteer abroad, to start a business, experience the “real world” — only to return to their daily reality.

The wolf reminds us that the wild exists, even if we can’t fully inhabit it. It inspires us.

The Linoleum

As the film comes to a close, Fox and the gang get back to the sewers after saving Kristofferson. Realizing the entire community remains at risk since their homes are destroyed and they can’t go above ground, they discover a sewer line that ironically leads directly underneath a grocery store — aptly called “Boggis, Bunce, and Bean International Supermarkets.”

Elated and running about the store afterhours, Fox and Felicity share a moment. Felicity reveals she’s pregnant again. Then Fox delivers the film’s core thesis under the store’s fluorescent lighting, surrounded by his family and friends.

“They say all foxes are slightly allergic to linoleum, but it's cool to the paw, try it. They say my tail needs to be dry cleaned twice a month, but now it's fully detachable, see? They say our tree may never grow back, but one day, something will. Yes, these crackles are made of synthetic goose and these giblets come from artificial squab and even these apples look fake—but at least they've got stars on them. I guess my point is, we'll eat tonight, and we'll eat together. And even in this not particularly flattering light, you are without a doubt the five and a half most wonderful wild animals I've ever met in my life.”

The setting is deliberate. Supermarkets, with their processed foods and sterile aisles, are our temples to synthetic abundance. Yet Fox finds meaning in it not by denying the artificial but by embracing what remains wild in him and his family and friends — love, community, resilience. He neither pretends to be the wolf, nor mourns the proverbial — and occasionally literal cage — he and they are living in. He celebrates the balance he’s been able to forge, underscored by the rebellious and violent ordeal they just suffered, which was of course all his fault. He’s now able to provide for his growing family while honoring their shared wild heart.

The linoleum floor, the fluorescent lighting, the performative and signaling materiality of modern life (the detachable tail), the artificial food (but has stars on it)…these are metaphors for the imperfect modern society we’ve created, as a substitute for the wild and chaotic one we used to have. Following modern society’s rules — getting that “W2 job”, the mortgage, asking HR for time off, jumping through hoops of credentialism — it’s unnatural and irritating, but it’s functional and necessary for most. Fox’s acceptance of this reality — which required a lot of pain and self-exploration — paired with pride in his “wonderful wild animals” suggests success lies in carving out some degree of authenticity within the constraints modernity place upon us.

At the end of Fox’s speech, Ash says “that was a good toast” and then turns on his own Walkman clipped to his waist. Music starts playing. And Fox smiles.

Living with the Tailhole

So, Fantastic Mr. Fox is a story of navigating modernity’s tensions between who we are and what society demands of us, between the thrill of the hunt and the comfort of the cage. Fox growls in an office but buys the tree. He wears a suit, but his tail sticks out. He fears the wolf, but salutes him. He steals, lies, and endangers, yet provides, loves, and grows. He is you. He is all of us… straddling two worlds, performing but surviving.

The film offers no easy answers. Fox doesn’t escape the cage or fully surrender to it. He finds meaning in small victories — a shared meal with family, a community digging together, a moment of connection with a distant wolf. His journey invites us to embrace our tailhole moments… sparks of rebellion or creativity leaking through our polished lives. Perhaps it’s a novel drafted in stolen hours from work, a side hustle launched on a whim that nobody knows about, or a refusal to play Whack-Bat by the rules.

Like Fox, we might find freedom not in dismantling the system but in carving out space within it — raising a fist to our wilder selves out there, even as we walk the linoleum aisles. As he says, “We’ll eat tonight, and we’ll eat together.”

For some wild animals, that’s enough. For others, it’s a start.