The Monty Hall Proof

A mathematical reason to switch life paths — even when it doesn’t feel right (or make sense to others)

I’m in the middle of writing a longer, I think powerful series about mindsets, frameworks, and real-world examples of how to build a simple consulting or solo business — and carve out a little more freedom for yourself and your family.

It’s not a playbook. It’s an anti-playbook. It’s inspiration mixed with memoir.

I’ve had a few readers ask me for it and it’s coming. But while writing it, one mindset grew to deserve its own piece. This is that piece.

It’s about how we make decisions. And how most people are trained to get it exactly backward. Even when the math says otherwise… especially when the math says otherwise.

This is the Monty Hall Problem — and it might just be the most important concept you've never fully internalized let alone heard of.

The Monty Hall Problem

You might remember it from the movie 21, based on the true story of the MIT blackjack team, starring Kevin Spacey. There’s a moment where Spacey — playing a statistics professor — breaks down a classic probability puzzle tied to game theory called the Monty Hall Problem.

Here’s how it works:

You’re on a game show. You’re presented with three closed doors. Behind one of them is a brand new car. Behind the other two are goats.

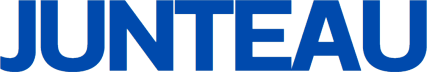

You think to yourself — correctly — that you have a 1 in 3 chance (~33%) of picking the car. There’s no information to go off of, so you make a random choice — say, Door #1.

Then Monty Hall — the host, who knows what’s behind each door — opens one of the other doors, say Door #3, and reveals a goat. Now he gives you a choice:

Stick with your original pick, or switch to the remaining unopened door.

Most people think:

Now there are only two doors left. It’s 50/50 now. And my odds actually improved, so I’ll stick with my original pick.

Wrong.

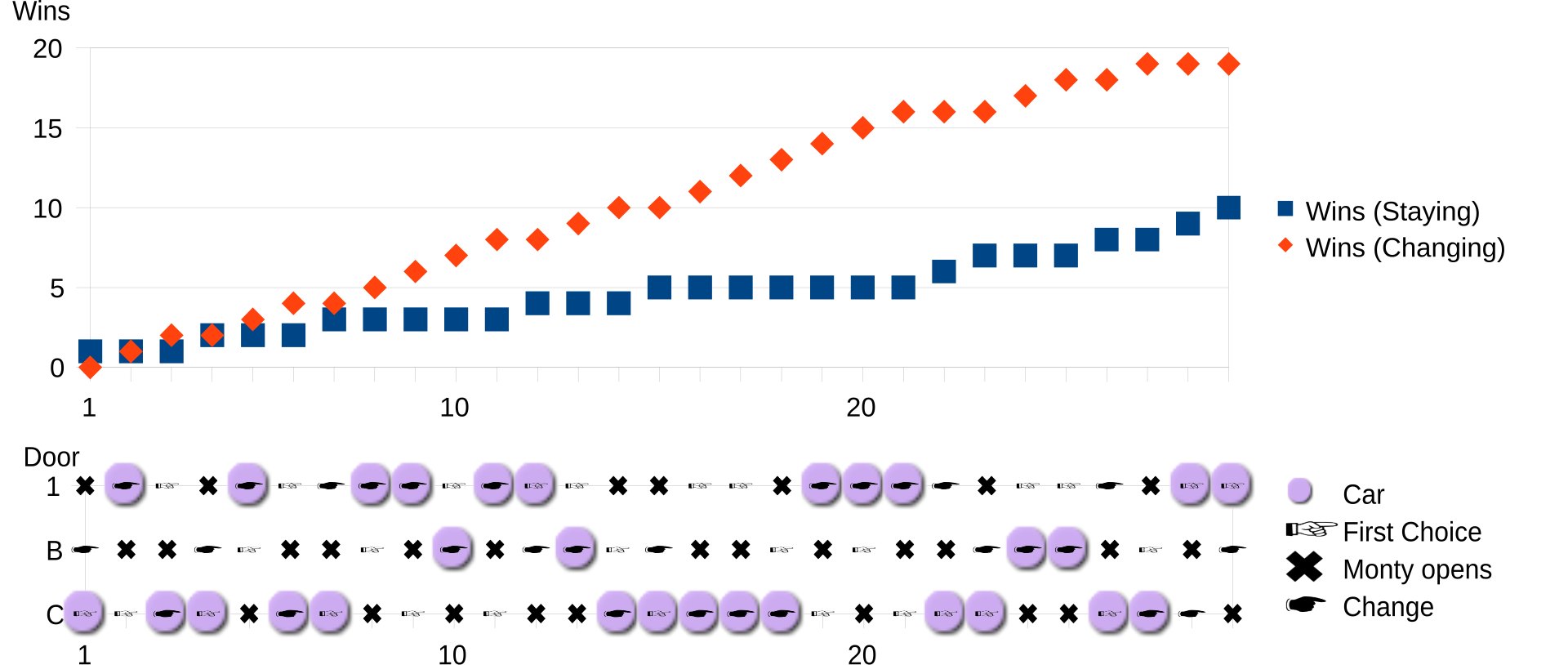

You should switch doors every single time.

Here’s why…

The odds of your original choice — Door #1 — having the car are, and always will be, ~33%. The reveal of new information doesn’t change the initial odds — it just gives you insight into the likelihood of other possibilities working out better. When Monty reveals one of the losing options, he’s effectively handing you the combined odds of the two remaining doors.

Think of it this way: at the beginning, the two doors you didn’t choose had a combined 2 in 3 (67%) chance of having the car. Monty knows what’s behind each door and always reveals a goat — meaning he’s essentially guiding you away from the wrong option and toward the better one. By switching, you're now choosing that combined probability, and your odds jump from ~33% to ~67%.

Your odds of success will never change if you stay put.

But you double your odds of success by being willing to switch.

Most people don’t understand this puzzle. Admittedly, it takes some pondering to “get it” — because it violates our gut-level intuition. That’s why there was an entire movie scene about this problem specifically — just pondering it can be dramatized in film. But once you do get it, it becomes an incredibly powerful framework for making decisions in your life.

So what’s the real-world application?

Most people pick a “door” in life early — a college major, a job, a city, a lifestyle, a relationship — and then stick with it. Even when new information comes in. Even when better options appear. Even when something is clearly revealed to “be a goat.”

In fact, many people see the failure or irrelevance of other options — the revealed goat — as validation that their original choice was the right one all along. But it’s the opposite. Fear of switching is a deeply human response, rooted in safety and sunk cost bias. But it’s just your base-level programming.

The people who win — the ones who create momentum, build leverage, and find more fulfilling paths — are the ones willing to re-evaluate and switch.

The Monty Hall Problem is about doors… and whether you’re willing to open another one.

Especially when it doesn’t make obvious sense at first glance.

Your life is like a game show where the doors — opportunities — are constantly appearing and disappearing. Sometimes they’re only open for a sliver of time. And there are far more than just three — they come in infinite shapes and sizes, and they’re always in motion.

It’s less like a glitzy game show and more like that scene from Monsters Inc., where all the doors are hanging like laundry at a dry cleaner, flying by in every direction. The winners aren’t the ones who cling to their first pick. The winners are the ones who are willing to switch when the goat is revealed — not because it feels safe, but because it’s statistically, strategically, and spiritually smarter to do so.

As for what “success” or “winning” really means… well, that’s another essay.